Jewish Heritage

Report

Vol. I, Nos. 3-4 / Winter 1997-98

Cuban Architecture

Tropical Remnants: The Architectural Legacy

of Cuba's Jews

by Paul Margolis

Exterior

of Temple Beit Hatikvah, Santiago de Cuba. For many years, this

synagogue was used as a cultural center by the city. In 1995,

it was returned to the Jewish community and re-dedicated. Photo:

Paul Margolis.

Exterior

of Temple Beit Hatikvah, Santiago de Cuba. For many years, this

synagogue was used as a cultural center by the city. In 1995,

it was returned to the Jewish community and re-dedicated. Photo:

Paul Margolis.

Cuba was home to a viable Jewish community for only

a brief period of time in the 20th century. In the late 1950s,

before Fidel Castro came to power, some 15,000 Jews lived in Cuba.

Most of them had settled in Cuba during the first decades of the

century; many had become comfortably middle-class, some quite

prosperous. All of that changed after 1959, when Cuba became a

Communist country. Over 90% of the Jews fled, mostly going to

the U.S. By the early 1990s, the Jewish population of Cuba was

estimated at 1,000 to 1,200.

Cuba's Jews are primarily Eastern European Ashkenazi, with Sephardic

Jews from Turkey making up the balance of the community. The first

Jews in Cuba in this century came to do business after the United

States defeated Spain in the Spanish-American War of 1898, and

Cuba became a sort of U.S. protectorate. The Eastern European

Jews tended to use Cuba as a way station into the U.S. in the

1920s, when restrictive laws made immigration into this country

more difficult. It was possible to go to Cuba, wait six months

to get a Cuban passport, then go directly to the U.S. Some Jews

stayed in Cuba, others were stranded there by even more stringent

immigration restrictions, or by the outbreak of the Second World

War after which few thousand Holocaust survivors settled in Cuba.

The Sephardic Jews came mostly from Turkey after 1918, during

the political upheaval that followed Turkey's defeat in the First

World War. The Jews who remained in Cuba after the Castro-led

Revolution tended to be assimilated, intermarried and supporters

of the government. A high percentage were professionals who enjoyed

status and comfortable lives. In 1991, in the wake of the near-collapse

of the Cuban economy, the government allowed more freedom of religious

observance. Jews began attending synagogues and learning about

Judaism for a variety of reasons. Some did it out of a genuine

spiritual hunger, others because of the need to be with one's

own group in difficult times, and still others from opportunistic

motives.

I traveled to Cuba twice in 1994, and again in 1996, to document

the rebirth of Judaism on the island. While my primary interest

was photographing and interviewing the Jews to report on their

lives, I also visited Jewish sites in all of the major cities

of Cuba. Havana, which is home to the majority of Cuba's Jews,

has three synagogues in varying states of use, two cemeteries,

and a kosher butcher shop. Like nearly all of Cuba's buildings,

except for those spruced up for the tourist trade, the Jewish

sites suffer from nearly 40 years of a lack of maintenance. Havana

also boasts one of the stranger Jewish monuments in existence

anywhere: a memorial to Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, the American

Jewish couple who were executed for attempting to pass atom bomb

secrets to the Soviet Union.

The Patronato Synagogue, in the Vedado section, was built in the

mid-1950s by Havana's newly affluent Jews. It is hardly architecturally

inspiring: the building resembles a shoe box with a McDonald's-like

arch in front. The Patronato is both the cultural and religious

center for Havana's Jews. The Jewish Joint Distribution Committee

maintains an office in the building, there is a library, and classes

and social activities are held here. The Patronato is the synagogue

to which groups of Jews visiting from overseas are usually taken

for Friday night services. Recently the Patronato affiliated with

the Conservative movement in the U.S.

Temple Adath Israel in Old Havana is a more modest structure,

also dating from the 1950s. A simple concrete building, almost

unnoticeable from the crowded, narrow street, it is Havana's Orthodox

shul. During the years when religious observance was discouraged,

small groups of mostly elderly people attended services here.

In late 1994, the first Orthodox bar mitzvah in 30 years was held

there.

Havana's earliest synagogue, Chevit Achim in Old Havana, dates

from 1914. It is located in what was once a meeting hall and is

hardly ever used. A Reform congregation meets sporadically in

what was once a Sephardic cultural center in the newer part of

the city.

There are two Jewish cemeteries, an Ashkenazic and a Sephardic

located in Guanabacoa, a town outside of Havana. Both are reasonably

well maintained these days, with a caretaker who sees to their

upkeep.

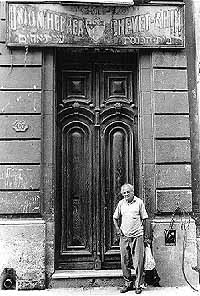

Temple

Chevet Achim, in Old Havana, was founded in 1914 and is Cuba's

oldest synagogue. Daniel Esquenazi, shown standing in front of

the seldom-used synagogue, is both shammes and president of the

congregation. Photo: Paul Margolis.

Temple

Chevet Achim, in Old Havana, was founded in 1914 and is Cuba's

oldest synagogue. Daniel Esquenazi, shown standing in front of

the seldom-used synagogue, is both shammes and president of the

congregation. Photo: Paul Margolis.

Small pockets of Jews live outside of Havana, in the

cities of Santiago, Camaguey and Cienfuegos. In Santiago, at the

far end of the island, the community of about 100 Jews got its

synagogue back in 1995, after a 25-year period during which the

building had been used as a youth center. The shul was re-dedicated

in July of 1995, and regular Friday night services are held there.

A small cemetery with graves dating back to the 1920s is located

about a half-hour drive from Santiago.

In Camaguey, a dusty city in the center of the island, the synagogue

was taken over by the government and turned into apartments and

a clinic in the 1960s. The community of 75 or so Jews is still

waiting to either receive another building from the municipality

or to be able to buy their old synagogue from the municipality.

The Camaguey Jewish cemetery has been refurbished, cleaned and

maintained over the past several years with funds made available

by the government and from overseas Jewish agencies.

Cienfuegos is a port city some 200 miles south of Havana with

a tiny Jewish community. When I first visited in 1994, there were

35 Jews. However, I have since heard that half the community emigrated

to Israel. The few remaining Jews meet in each other's homes for

holidays, or go to Havana.

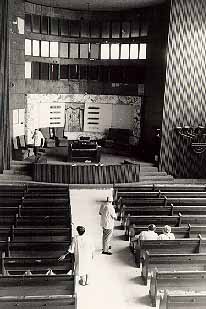

Interior

of the Patronato Synagogue, Havana. The Patronato was once Havana's

upscale shul, built by newly affluent Cuban Jews in the early

1950s. Today the synagogue is affiliated with the Conservative

movement in the U.S. and serves as the focal point for most Jewish

activities in Havana. Photo: Paul Margolis.

Interior

of the Patronato Synagogue, Havana. The Patronato was once Havana's

upscale shul, built by newly affluent Cuban Jews in the early

1950s. Today the synagogue is affiliated with the Conservative

movement in the U.S. and serves as the focal point for most Jewish

activities in Havana. Photo: Paul Margolis.

Near Cienfuegos, in Santa Clara, there is a Jewish

cemetery, but few or no Jews live in the nearby city. The Santa

Clara cemetery was at one point being refurbished by a private

organization, but recently I heard that funding had stopped, and

building materials had been stolen from the site. Like Cuba itself,

the Jewish sites there are in a state of limbo. The U.S. economic

embargo makes it difficult for American Jews to aid Cubans, and

the lack of funds hampers importation of building supplies from

other countries. Members of the small Cuban Jewish community have

been emigrating to Israel in a trickle, thus reducing the numbers

of people who are interested in preserving their sites. The future

of the Cuban Jewish community--and that of the Jewish sites on

the island--depends on the political and economic situation.

Paul Margolis is a writer and photographer who reports on little-known

aspects of Jewish life. His e-mail address is: pmrgwrtr@chelsea.ios.com.

To view more photos by Paul Margolis and a wide selection of information

about the Jews of Cuba consult http://jewishcuba.org

Contact the Editor

of Jewish Heritage Report

http://www.isjm.org/jhr/nos3-4/cubarch.htm

Updated: 23-July-98