BOOK REVIEW

A Refugee's Emotional,

Ethnic Awakening in Her Native Cuba

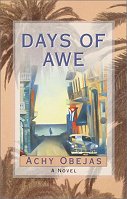

DAYS OF AWE

By Achy Obejas

Ballantine $24.95, 384 pages

By PAULA FRIEDMAN,

SPECIAL TO THE TIMES

Two years after the

revolution, Cubans began leaving the island on anything that would

float--less terrified of Castro's communism, novelist Achy Obejas

intimates in "Days of Awe," than they were of the persistent rumors

that an invasion and a terrible war would follow. As Obejas' narrator,

Alejandra explains it, Cubans feared that their country would be besieged

by "another one of those bloody skirmishes the U.S. periodically undertook

in Latin America." With much sadness, but little hesitation, Alejandra's

parents shipped out in April of 1961 with their 2-year-old daughter

in tow, stopping first in Miami, but finally settling in Chicago,

where Lake Michigan provides the family with a bit of watery solace

that reminds them of their homeland. As Alejandra grows up, she begins

to grasp her parents' passionate attachment to their home country,

learning as well about their all-but-dormant Jewish roots. Obejas

takes the novel's title from the English translation of the Hebrew

"Yamim Nora'im," the time between Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur, those

religious "days of awe." But Obejas wisely holds back this explanation

until late in the novel after the reader has ample time to absorb

the process of awakening that Alejandra undergoes about her own nationality

and faith. While both her parents, Nena and Enrique, were born to

Jewish families, neither was raised Jewish. Both of their families

had turned from their Jewishness as anti-Semitism swept Cuba during

and after World War II. Later, in Castro's Cuba, it was simply better

to claim no religious faith at all.

An interpreter and

oral translator, Alejandra makes her first trip back to Cuba in 1987

for professional reasons, working for a group of progressive Chicago

politicians and activists. But her parents' response to her travel

plans leaves her unsettled: "My parents are not fanatical refugees,

they do not assume everything about the revolution is hideous. As

much as they may be alienated in the U.S., they've made peace with

the difficult decision to leave Cuba. Yet, when I said I was going

back to the island, they paused as if they needed a moment to adjust

their antennas, to rearrange their sense of disbelief into something

coherent and civil. Then they kicked into exile-style paranoia.

"'Be careful--don't

talk to just anyone,' my mother warned me about my upcoming visit.

'You will get them into trouble if you talk to them.' ... 'You could

get yourself in trouble,' my father said. 'You could wind up in jail."'

Waiting to go through

processing in the Havana airport, Alejandra realizes that she hadn't

been entirely honest with herself about her reasons for visiting Cuba.

The truth was that this trip marked for her a "return to the Land

of Oz" she'd conjured in her dreams. With subtlety and grace, Obejas

depicts Alejandra's intensifying awareness of her own identity, as

a Cuban, a Jew and a woman.

Visiting

family and friends, Alejandra encounters a range of attitudes about

Castro's revolution, with some believing the man no more than a scoundrel,

and others seeing him as merely a flawed revolutionary. Given her

own parents' fear of the government, Alejandra is surprised to find

the various ways in which Cubans have made peace with their lives

under Castro. It would be easier for her to let go of her homeland

and return to America, the land where she was raised, she muses, if

she could see the world in blacks and whites.

Visiting

family and friends, Alejandra encounters a range of attitudes about

Castro's revolution, with some believing the man no more than a scoundrel,

and others seeing him as merely a flawed revolutionary. Given her

own parents' fear of the government, Alejandra is surprised to find

the various ways in which Cubans have made peace with their lives

under Castro. It would be easier for her to let go of her homeland

and return to America, the land where she was raised, she muses, if

she could see the world in blacks and whites.

Through Moises Menach,

Enrique's childhood pal, Alejandra learns about the complexities of

life in modern Cuba, and she also learns about her parents' ambivalent

ties to their own Jewishness. Obejas has created a true wise man in

Moises, a man who possesses vision, compassion and the fortitude to

carry on, despite hardship.

With Moises' son-in-law

Orlando (permanently separated from his wife, Angela), Alejandra experiences

a profound erotic awakening, feeling herself deeply in love for perhaps

the first time in her life. Obejas masterfully links identity with

place, language and the erotic life, without ever descending into

sentimentality.

Her descriptions render

her characters' emotional lives with a precision that precludes exotic

stereotyping. But the novel yields further delights, as Obejas allows

Alejandra to meditate on the cultural and philosophical differences

reflected in language.

We learn, for example,

that in Spanish, it is simply not possible to speak of love for an

object with the same word used to speak of human love. This focus

on language accounts for one of the novel's most enchanting riches,

revealing a capacity to neatly articulate in Spanish the concepts

that English and other languages have no words for.

Copyright 2001 Los

Angeles Times

Amazon.com